2.7K

Downloads

7

Episodes

How I Survived is a podcast about recreation at residential and day schools in Canada’s North that celebrates the strength, resilience, spirit, and creativity of former students and Survivors. How I Survived is a collaboration between the NWT Recreation and Parks Association and the University of Alberta. The research and podcast have been supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the NWT and Nunavut Lotteries, and the Government of Canada’s Department of Heritage.

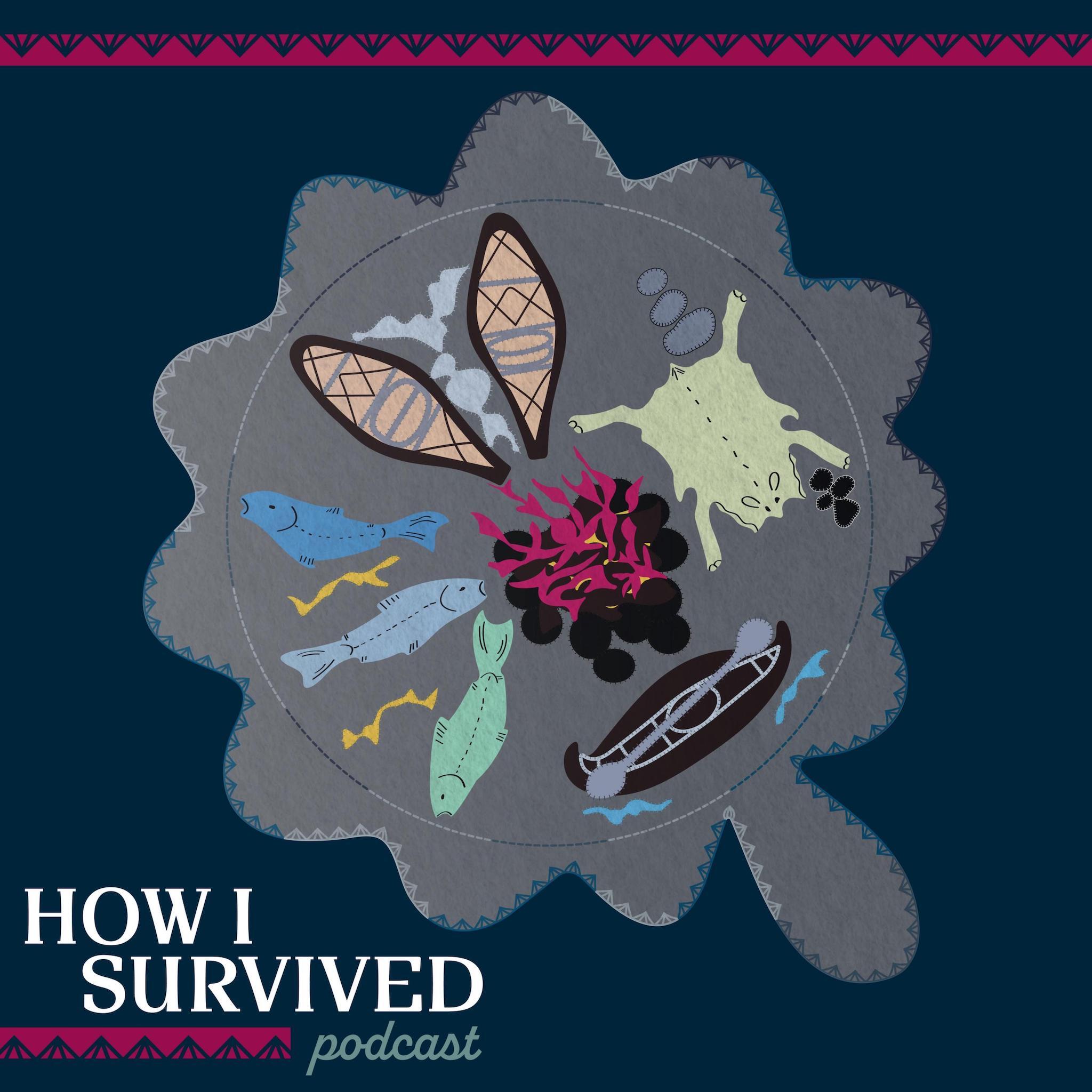

How I Survived is a podcast about recreation at residential and day schools in the Canadian North. Background This podcast grew out of a research project of the same name, which was initiated in 2018 by the NWT Recreation and Parks Association (NWTRPA) and Gwichyà Gwich’in historian Dr. Crystal Gail Fraser (University of Alberta). The purpose of the research project is to gather and share the stories of residential and day school Survivors about recreation. It provides Survivors with an opportunity to share their experiences with the public and will also preserve their stories for future generations. This project and podcast celebrate the strength, resilience, spirit, and creativity of former students. We hope it will also provide a new way of understanding the history and legacy of residential and day schooling in the North and inspire forward-looking dialogue. The Project Team How I Survived is guided by an advisory committee that includes former Grollier Hall student and CBC journalist Paul Andrew (Shúhtaot’ı̨nę); elite cross-country skier and residential school Survivor Dr. Sharon Anne Firth (Teetł’it Gwich’in); long-time teacher Lorna Storr from Akłarvik (Aklavik); and filmmaker and photographer Amos Scott (Tłı̨chǫ). The project co-leads are Dr. Crystal Gail Fraser from the University of Alberta and Jess Dunkin from the NWT Recreation and Parks Association. Rebecca Gray is the project's research assistant. You can learn more about the project team here. The Cover Art The cover art for the How I Survived podcast is based on a wall hanging made by Agnes Kuptana, a residential school Survivor, artist, and educator from Uluksaqtuuq (Ulukhaktok), Northwest Territories. The wall hanging is in the shape of an Inuvialuk drum. At the centre of the drum is a campfire, which is a place of community, warmth, sustenance, storytelling, and sharing knowledge. Around the campfire are four seasonal activities: spring hide tanning, summer kayaking or canoeing, fall fishing, and winter snowshoeing. The wall hanging that Agnes designed and sewed represents some of the things that gave Indigenous children from across the NWT strength and helped them survive residential and day school: the Land, culture, way of life. Agnes passed away in July 2025. Her story lives on in episode six of the How I Survived podcast. Quyanainni, Agnes. Our Theme Song The theme song for the How I Survived Podcast is "Love the Light." It was written and performed by K’áhsho Got’ı̨nę singer-songwriter Stephen Kakfwi. Stephen is a Survivor of Grollier Hall, Akaitcho Hall, and Grandin College. Photo: Stephen Kakfwi. Credit: The Pew Charitable Trusts. This song was recorded as part of the Gho-Bah/Gombaa (First Light of Day) Project in 2017. The project, which was led by Juno Award-winning Sahtúot'ı̨nę singer-songwriter Leela Gilday and which featured artists from across the NWT, explored reconciliation through song. Photo: The Gho-Bah/Gombaa performers at the Northern Art and Cultural Centre, 2017. Credit: CBC North.Episode 1 - Introducing How I Survived

Season 1 Institutions and Communities

If you are a Survivor or intergenerational Survivor of residential school or day school and need help, there's a free 24-hour support line. Call 1-800-925-4419.

Episode Credits

Host: Crystal Gail Fraser

Guests: Crystal Gail Fraser, Jess Dunkin

Producers: Amos Scott, Jess Dunkin

Editor: Jess Dunkin

Audio Engineer: Brandon Larocque

Theme Song: Stephen Kakfwi

Episode Transcript

Crystal Gail Fraser

[Introduction in Dinjii Zhuh Ginjìk.]

My name is Crystal Gail Fraser. With Paul Andrew, I am the co-host of How I Survived. This is a podcast about recreation at residential and day schools in northern Canada.

In this episode, you will hear about abuse and trauma. Please look care of yourself as you listen.

If you are a Survivor or an intergenerational Survivor of residential or day school, and need help, there's a free 24-hour support line. Please call 1-800-925-4419.

Jess Dunkin

How I Survived is a project about recreation at residential and day schools in the Canadian North. The project was designed to give Survivors an opportunity to share their experiences while at residential and day school with the public. We also wanted the project to preserve Survivor stories for future generations. And our focus was really on celebrating the strength, the resilience, the spirit, and the creativity of children who were institutionalized at residential and day schools in the NWT.

My name is Jess Dunkin. I'm a settler historian and writer. Since 2018, I've been the project manager for How I Survived, on behalf of the NWT Recreation and Parks Association.

The NWT Recreation and Parks Association, or the NWTRPA for short, is a non-profit recreation organization based out of Sǫ̀mba K'è, in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, which is in Treaty 8 territory, the homeland of the Yellowknives Dene and the North Slave Métis, but that works with communities across the Northwest Territories.

For more than 35 years, the NWTRPA has been promoting recreation and supporting leaders, communities, and partners in the territory through training, advocacy, and networking.

After the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, or the TRC as it's more commonly known, released its final report in 2015, the NWTRPA made a commitment to advance truth and reconciliation in the North and in the recreation sector by working in the spirit of the TRC. Um, I say in the spirit because the 94 calls to action don't explicitly address recreation, but they do provide guidance for how we should be working as do things like the United Nations Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, or UNDRIP, and the Calls to justice of the inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

In 2017, we reached out to Dr. Crystal Gail Fraser to talk about recreation and residential schooling in the Mackenzie Delta at our annual conference, which that year happened to be in Inuvik, which is in the Delta.

Crystal

How did I start researching the history of residential schools? That's actually a unique story. I had just done a master's in Canadian history and I was more interested in the history of marriage, childbirth, and midwifery among our people. And I always knew that my research was going to be community engaged, that I wanted to do work that was important to my people and my nation. And, and so a part of that, is sharing your interests, talking about the research. And pretty quickly, I was redirected towards the history of residential schools.

I was pretty scared. This would have been in about 2012, so during the same time as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, but residential schools were not a part of the Canadian national narrative yet, and many Survivors had not yet started that journey of healing, of grappling with their own story. And so I hesitated because I didn't want to cause harm, even though I had many people telling me how important this topic was. So I started out slow and mostly through visiting, um, and just had, had so many supporters and so many people involved along the way.

I have a book coming out later this year. It's called By Strength We Are Still Here, Indigenous Peoples and Residential Schooling in Inuvik and it is based on the PhD thesis. By Strength We Are Still Here really looks at the experiences of Indigenous children at Grollier and Stringer Halls in Inuvik. Those institutions opened in 1959. Basically I trace student experiences at those institutions when they attended Sir Alexander Mackenzie School and Samuel Hearne Secondary School.

Every Survivor I interviewed, everyone who I talked to the experiences were mostly horrific.Trying to honor those experiences of violence and, and talk about them, but then on the other hand, honor the other side of the narrative that focuses on the strength and the resilience, and how children got through it.

Jess

Crystal's presentation was a really eye-opening experience for the board and staff of the organization. We had these discussion circles afterwards and it made really clear, uh, the need for education related to histories of residential and day school and in particular, um, amongst people who themselves are directly impacted by residential and day school.

It was after that conference that the NWTRPA approached Crystal and said, Would you be interested in collaborating on a project to gather and share the stories of Survivors? And the focus of the project would be on recreation. And we were really fortunate that Crystal said yes.

Crystal

What is recreation? We understand recreation to include the creative and the physical, but also the social and the intellectual. These may include music, The arts, sports, crafts, and sewing, reading, games, and Girl Guides and Boy Scouts.

Jess

I think first and foremost it's important to study recreation at residential and day schools because Survivors have told us that it was part of their experience and it's something that they want to talk about and share.

I think it's also important, um, because it allows us to see residential schooling from different perspectives and in different lights. So on the one hand, it's useful because it reveals the assimilationist goals of the system. So the ways in which residential schooling was meant to turn Indigenous children into white children. It also, at the same time, reveals what we talked about earlier. So the strength, the resilience, the spirit, and the creativity of the Indigenous children and youth who were institutionalized in that system.

Lastly, I think it's an important topic because it's one that most Canadians don't know anything about. For that reason alone, it's something that we should be studying.

One of the goals of How I Survived is to center the voices and experiences of Survivors of residential and day school. We wanted to make sure that Survivors and intergenerational Survivors were at the forefront in all aspects of the project. So, designing the project, identifying who should be interviewed, undertaking the interviews.

And so to make sure that we were doing this, we created an advisory committee. With the exception of myself and the executive director for the NWTRPA, all of the advisory committee members are Survivors and intergenerational Survivors.

And so I'll just really briefly introduce each of them because they've all been such an important part of this project.

Paul Andrew is Shúhtaot'ı̨nę from Tulı́t'a. Paul was first taken to residential school when he was eight years old. He spent seven years at residential school. He went on to work as a journalist with the CBC for almost 30 years.

Dr. Sharon Firth is Teetł’it Gwich’in from Aklavik. Sharon and her twin sister, Shirley, learned to ski with the Territorial Experimental Ski Training Program while at residential school in Inuvik. The first sisters went on to compete in four Olympic winter games and three world championships.

Lorna Storr was born in Aklavik and raised in Teetł’it Zheh. She first went to residential school when she was six years old. Lorna began working as a teacher at Moose Kerr School in Aklavik in 1974. In 2014, she was inducted into the NWT Education Hall of Fame.

Amos Scott is a Tłı̨chǫ Dene filmmaker and photographer. He started his career in journalism. Amos is one of the founders of Dene Nahjo, a Dene innovation and arts collective, and the principal of Adze Studios, which helps organizations and businesses produce high quality HD videos and digital content

In 2022, Rebecca Gray, who is Dehcho Dene, Scottish, and Ukrainian, joined the project as a research assistant.

Crystal

How I Survived is important for a number of different reasons. First and foremost, the fact that we have a steering committee, that we are Survivor- and Indigenous-led, I think that is really important. Even though How I Survived is embedded in research and it is a partnership between the NWT Recreation and Parks Association and the University of Alberta, we really get direction from community and I say that because we know that Indigenous communities. Especially in the North, have a long history of being exploited, of having research models that are based on extraction. My hope is that we're providing a different model that is based on, on people and their needs and human experiences.

Secondly, I think How I Survived is important because we still don't know all there is to know about residential schools, especially in the North. There are very few people engaged in that work in the North. Something like sport and recreation at residential schools, what we do know has been purely southern focused. And so I see this as a really rich topic. Every time we talk to people about it, it's storytelling that is always the highlight of the conversation, and it is relationships.

And so I guess that would be my third point, for How I Survived, the importance of it, is the relationships that we build, that this is not an isolated project, that we want to be out there doing this work, sharing the funding that we have for the project, and seeing some good come out of it.

Jess

How I Survived actually came out of an early meeting of the advisory committee. Um, we were talking about possible names for the project and Paul Andrew, who's a Survivor of Grolier Hall, spoke about the ways in which recreation, but specifically music and skiing, were a lifeline for him when he was at residential school in Inuvik. And in his words, he said, recreation was how I survived. The other committee members that were there that day, I think, felt similarly and they sort of echoed that sentiment as they shared their own memories of residential school.

We're really conscious of the fact that not all former students have positive memories of recreation. You'll hear from Survivors in this podcast about the negative impacts and aspects of recreation. You'll hear about how students were forced to participate in certain kinds of activities. And you'll hear about how things like the introduction of competition had really negative consequences for relationships between students.

By using that title, How I Survived, we're not trying to erase the range of experiences that students had. To the contrary, it's always been really important for us to capture the diversity of student experiences of recreation while they were at northern residential and day Schools. So the good and the bad.

The other thing that it's really important to acknowledge is that how I survived emphasizes the individual when we know that making it through residential school was very much a team effort. That's really clear in Agnes Kuptana's interview. She talks about the ways that children and youth took care of each other. We also really hear that come through in Sharon Firth's episode when she talks about the support that she and her sister Shirley provided to one another.

So, all this to say that the name of the project and the podcast, How I Survived, isn't meant to be a definitive description of student experience by any stretch, but rather we see it as an invitation to learn, to start important conversations about recreation at residential and day school in a respectful way.

Crystal

The first residential school opened in Fort Providence in 1867. I'll share some context for residential schooling in the North in the late 19th and early 20th century.

During this time period, particularly children from my region, the Gwich'in settlement area, and other regions of the High Arctic, they would have an extremely long journey to the residential schools in the southern Northwest Territories. So, Fort Providence, Hay River, possibly Fort Resolution. And that was several thousands of kilometres by boat. There are Survivor stories about that experience, highlighting the intensity of that trip.

We also know that these institutions could not run without the children. And so even though it was called a school, there unfortunately was not a lot of learning happening. And so children would engage in some activities that were familiar to them, such as harvesting ice in the winter, getting wood for fuel, going out on the Land to pick berries to supplement their diet, but this kind of labor was done under very strict and harsh conditions.

We know that the education that these children did receive at residential schools, so maybe a few hours a day, maybe, was largely focused on the British Empire. So they were learning the same content at northern residential schools as children were at southern residential schools. And so curriculum that was focused on Europe, it was focused on exploration narratives, it was focused on farming, pretty irrelevant for the child who lives in the north.

We also know that children were forced to learn either French or English, also Latin, and they often experienced some form of oppression and violence if they spoke their Indigenous languages. Of course, there are Survivor stories about the persistence of them speaking languages, and this is why we're still able to speak our languages today.

Additionally, the residential schools in the North during these early years were quite similar to the ones in the South in the sense that they sought to eradicate the identities of Indigenous children. The way identities were taken away and reshaped would be through Christian names, not being allowed to wear your traditional clothing–so this sense of uniformity, through the wearing of the same clothes–and then of course, these early institutions was the segregation of children. And so you had residential schools that were Christian, but they were split up into Roman Catholic or Anglican. Maybe that was thefirst way that your family was split up, was through religion. And then once you actually get to the institution, you were then further divided by gender, so boys and girls were segregated, but then additionally, at a lot of institutions, you were then further split up by age. That really speaks to the whole point of trying to break up families.

Children who were institutionalized at residential and day schools in the late 19th and early 20th century were able to engage in recreational activities, but that time period looked a little bit different than later time periods.

There was very little time for recreation to begin with. These institutions, basically operated on the backs of children, their labour was required for everything to run smoothly and efficiently, and that's what took up a lot of their time, working. They then had a few hours a day for school, but also a few hours a day for church and praying and other kinds of religious activities. So again, not a lot of time at these early institutions for recreation.

However, there were some recreational activities that were available to them. Stories and photographs and archival documents do refer to some sports, such as football and baseball. There were also some organized recreation, such as Girl Guides and Boy Scouts, as well as music and band practice. And there are some photographs of children playing on playgrounds.

But really in this earlier time period, we know that approaches to recreation were unorganized. It was not really backed by any kind of organized curriculum or funded in a way that would allow it to succeed.

The 1940s and 1950s were really sort of a game changer for approaches to residential schooling. In the late 1940s in the House of Commons, the Canadian government decided that the residential school system needed to be closed. They needed to start to wind the system down, is what they said. And so that was the official federal approach, to start closing residential schools across Canada and get Indigenous students into provincial day schools. That did not happen in the North.

In the 1950s, the Canadian government really focused on the North as a place that needed a lot of intervention. We see brand new, multi-million dollar infrastructure being built all across the Northwest Territories for the purposes of educating Indigenous children. This included residential schools, it included Indian day schools, it included tent hostels and seasonal schools.

I'll talk about the area that I know best, and that would be the Gwich'in Settlement area.

So children who were institutionalized at the Aklavik schools–those schools opened up in the 20s and the 30s–were really embedded in this system that I described earlier. So forced labor, being separated from their families, attending church and being devout, not being able to speak their languages, being subjected to awful foods. Student narratives change with the opening of Grollier and Stringer Hall.

Now, I do need to say that the stories that have been shared with me about Grollier Hall are awful. And that was one of the most notorious institutions in Canada. So people do need to hear that still, I think.

With Grollier and Stringer, though, it was a little bit different in the sense that they left Grollier and Stringer every day to attend day school at Sir Alexander Mackenzie School and later at Samuel Hearne Secondary School. And so from the hours of nine to three, these children were able to physically leave the residential school and go to a day school with the other kids who lived in town. So I think having that break helped students.

Also these were brand new institutions, a lot of the labor was outsourced. They hired dishwashers. They hired cooks. They hired janitors. The institution came with a whole body of staff that was able to take on the hard labour that students once had to do, like in Aklavik. There was more, more flexibility there for students to actually do things that they wanted to be doing.

Additionally, again, we're in the High Arctic. These job postings were not attracting a lot of people. And so Grollier and Stringer Halls also hired local people. And it was immensely beneficial for a student to be able to see someone they knew, to have that person be the eyes for community, to run into somebody on the street and say, I saw your child today and they are okay.

Recreation looked different for children at residential schools from the 1950s onward. Again, I'm going to draw on examples from Inuvik because that is what I'm most comfortable with, but I think these examples are also characteristic of the broader residential schooling program across the Northwest Territories at the time.

Children who were at Grollier and Stringer Halls did leave those institutions every day for Sir Alexander Mackenzie School and Samuel Hearne Secondary School. And those recreation programs attached to the day schools were much more thorough, organized, better funded, it was actually part of a system.

Sport and recreation activities at the day schools were very well funded programs, in part for the white children who attended. There were many, many families in Inuvik who were non Indigenous, white families who were new to the North who belonged to this emerging labor force of RCMP, of teachers, of,government staff, of workers for the dew line, of construction people. These parents had certain expectations of what their child needed to gain at schooling. So a part of that was an abundance of sports teams. This was everything from floor hockey, to volleyball, to broomball, curling, boxing. There was so much available and some Indigenous students from Grollier and Stringer Halls actually became elite athletes through these programs.

Other forms of recreation at those residential schools include sewing and beading groups. They also include Girl Guides and Boy Scouts, as well as some cadet programs. Additionally, there was an emphasis on songs and music. We also know that at the day schools and at the residential schools in Inuvik, there were certain clubs and those too are a part of the recreation process.

Jess

We didn't always plan to make a podcast for this project. When we started, we actually thought we were going to make a traveling exhibit that was based on the stories that Survivors had shared with us. But then in April 2023, the advisory committee got together for the first time since before the pandemic, and one of the things that we talked about during that retreat was how we would share the stories that we had gathered to that point.

The committee was still interested in an exhibit, but they thought that we should consider other options that were maybe a little less labor intensive, a little less complicated. And so they directed us to make a podcast. And I think a podcast made sense to them for a few different reasons. It was accessible first of all, and I think that that's really important. So podcasts are free to anyone with a smartphone or access to the internet. But we also knew that the episodes could be broadcast as audio stories on community radio stations, which are still a really important way to share information and stories in the North. So it meant that the, um, The stories that Survivors were sharing with us, the recordings, could have a wider reach.

I think they also like the idea of a podcast because it would allow listeners to hear directly from Survivors about their experiences and in their own words.

The cover art for the How I Survived podcast features a wall hanging by Inuvialik seamstress and educator Agnes Kuptena. Listeners will have a chance to meet Agnes in episode seven of the podcast. The wall hanging that Agnes designed and sewed represents some of the things that gave children from across the NWT strength and helped them survive residential and day school. So the Land, culture, and way of life.

At the center of the drum is a campfire, which is a place of community, of warmth, of sustenance, storytelling, and sharing knowledge, and then around the campfire are four seasonal activities: spring high tanning, summer kayaking or canoeing, fall fishing, and winter snowshoeing.

The theme song for the How I Survived podcast was written and performed by a Survivor, K’áhsho Got’ı̨nę singer-songwriter Stephen Kakfwi. Stephen's a Survivor of Grollier Hall, Akaitcho Hall, and Grandin College. This song was recorded as part of the Gho-Bah project, which was led by Juno-award-winning Sahtúot'ı̨nę singer-songwriter Leela Gilday, and which featured artists from across the NWT explored the, um, the topic or the theme of reconciliation through song.

Listeners will notice that we switch hosts partway through the podcast. The first three episodes are hosted by Paul Andrew, who also did five of the six interviews. Unfortunately, partway through production, Paul was hospitalized. Paul remains a champion of the project, but he was unable to continue as the host of the How I Survived Podcast. Thankfully, Crystal agreed to step in so that we could finish the first season. We want to dedicate the first season of How I Survived to Paul Andrew.

In the following episodes, you'll hear from Rassi Nashalik, Dave Poitras, Beatrice Bernhardt, Ernie Bernhardt, Agnes Kuptana, and Dr. Sharon Firth.

Crystal

If you are a Survivor or intergenerational Survivor of residential or day school and you need help, there's a free 24-hour support line. Call 1-800-925-4419.

How I Survived is a collaboration between the NWT Recreation and Parks Association and the University of Alberta. The podcast is co-hosted by me, Crystal Gail Fraser, and Paul Andrew. I also provide historical direction.

How I Survived is co-produced by Amos Scott and Jess Dunkin. Advisory support is provided by Dr. Sharon Firth, Lorna Storr, and Paul Andrew. Our research assistant is Rebecca Gray. Haii’ to EntrepreNorth for sharing your recording booth with us.

Our theme song is “Love the Light” by Stephen Kakfwi. This episode also features music by Sean Williams. The cover art for this podcast was designed by pipikwan pêhtâkwan based on a wall hanging made for the project by Agnes Kuptana.

This podcast is produced with support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and NWT and Nunavut Lotteries.