2.7K

Downloads

7

Episodes

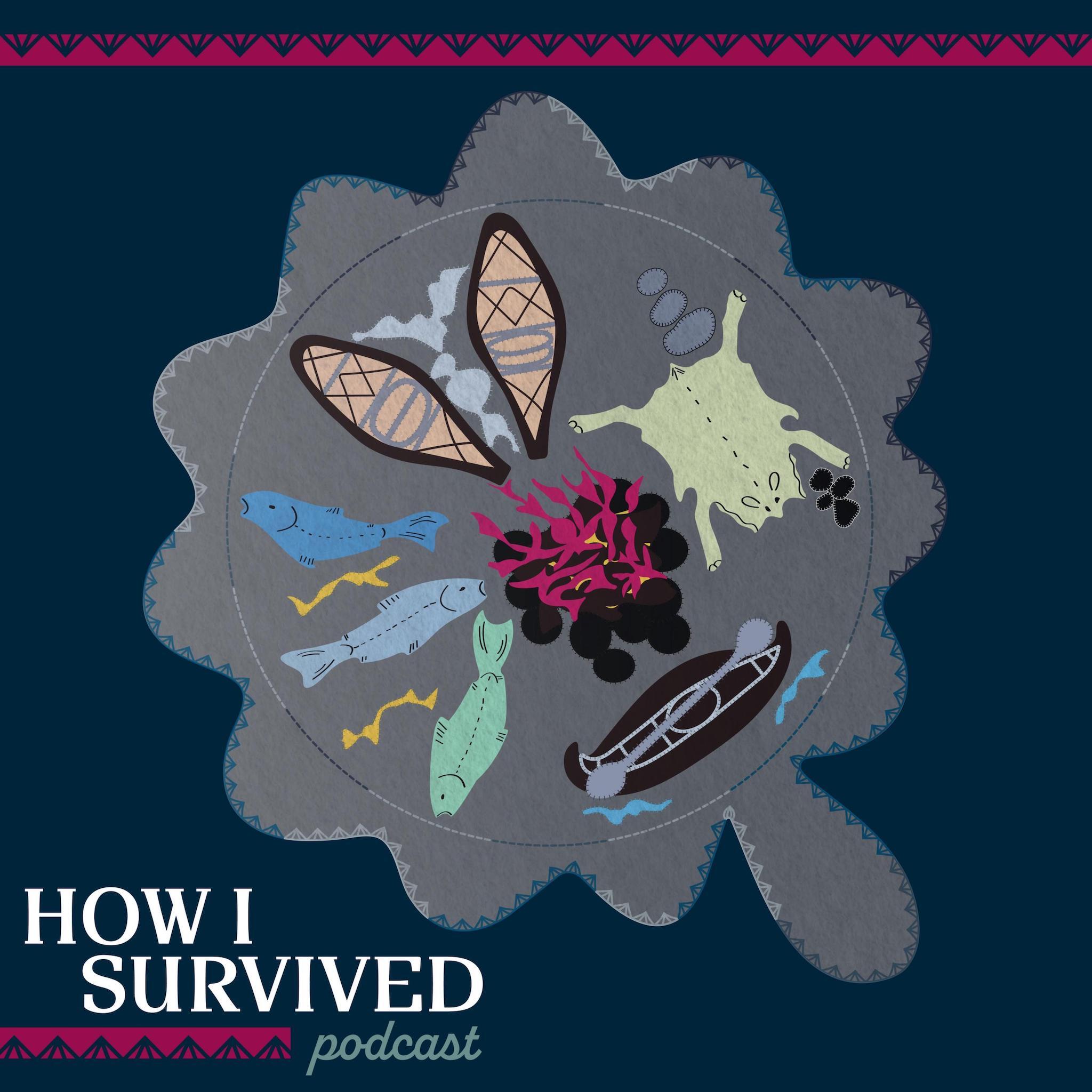

How I Survived is a podcast about recreation at residential and day schools in Canada’s North that celebrates the strength, resilience, spirit, and creativity of former students and Survivors. How I Survived is a collaboration between the NWT Recreation and Parks Association and the University of Alberta. The research and podcast have been supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the NWT and Nunavut Lotteries, and the Government of Canada’s Department of Heritage.

Episode 6 - Agnes Kuptana

Agnes Kuptana was a residential school Survivor from Uluksaqtuuq (Uluhaktok), Northwest Territories. She was also a talented seamstress and educator. Agnes made the wall hanging that is featured in the cover art for the How I Survived Podcast.

"When I was growing up, we lived in hunting camps. In the evening, we would listen to stories from our grandparents while scraping skins. They taught us how to make patterns and trace it out, and how to sew and stitch. They watched us closely. If we made a mistake, it was okay--they told us to keep sewing and that the next item would turn out better."

When we approached Agnes to create a wall hanging for How I Survived, she told us that she also wanted to be interviewed. Agnes wants young people to know about her experiences at residential school.

Agnes was born in an iglu and raised on the land, following the animals through the four seasons.

"It was beautiful. It was healthy, loving. There were lots of teachings. Every day was different and there was no fear. It's all in the language. There is lots of playing time and learning to do things. Chores, sewing. Sometimes you help your cousins go check the trap line, then you come back and you help elders if they want. You hitch up maybe one, two, three dogs and chop some ice from the lake or get water."

The only time Agnes saw white people was when they travelled to nearby Uluksaqtuuq.

When she was six years old, a plane came to Agnes's family's camp and took her away to residential school. For four or five years, she lived at the Coppermine Tent Hostel. She was also institutionalized at the Cambridge Bay Hostel and later at Stringer Hall in Inuuvik (Inuvik).

Coppermine Tent Hostel

The Coppermine Tent Hostel began regular operations in 1955. Located in what is now Kugluktuk, Nunavut, the hostel was operated by Anglican missionaries.

Left photo: Coppermine Tent Hostel, 1955. Credit: NWT Archives/Henry Busse fonds/N-1979-052: 0868. Right photo: Coppermine Tent Hostel, no date. Credit: NWT Archives/Northwest Territories. Department of Education, Culture and Employment fonds/G-1999-088: 0229.

From April to August, children lived in canvas wall tents stretched across wood frames. As Agnes describes, the tents were drafty and hard to heat. They were also easily damaged by high winds.

"[Our tent] had four beds with a small stove with a little oil tank in the back...and a door, which wasn't safe. The beds were just a sheet, blankets. So you can imagine if we did not sleep with our clothes, our parkas, our mitts, our mukluks, our hoods on, we would freeze to death. You heard children crying at night cause they're freezing."

At first, the children at the tent hostel came from the Kugluktuk area, but eventually, children from as far away as Uluksaqtuuq were brought there. The children attended classes at the local federal day school.

When the hostel closed in 1959, most of the children were transferred to the new residential schools in Inuuvik.

Agnes and Recreation at Residential School

Agnes wanted to be interviewed about her time at residential school because she wanted young people and future generations to know what she lived through. Agnes’s story is hard. It is marked by abuse and trauma. It is also a story of strength and persistence.

In her interview, Agnes shared that, in general, recreation had a negative impact on her life at residential school. But some of Agnes’s memories of recreation are different. She recalls, for example, the ways that she and other students used recreation to care for one another when they were hurting. Often, these were outdoor activities like going for walks or sliding, or activities that reminded them of home, like string games or picking berries.

This podcast is called How I Survived, but as Agnes's story makes clear, survival was a communal endeavour. Children made it through residential and day school because they looked after each other.

Agnes Kuptana passed away in July 2025. Her story lives on in episode six of the How I Survived Podcast. Quyanainni, Agnes.

If you are a Survivor or intergenerational Survivor of residential school or day school and need help, there's a free 24-hour support line. Call 1-800-925-4419.

Episode Credits

Host: Crystal Gail Fraser

Interviewer: Paul Andrew

Guest: Agnes Kuptana

Producers: Amos Scott, Jess Dunkin

Editor: Jess Dunkin

Audio Engineer: Brandon Larocque

Theme Song: Stephen Kakfwi

Episode Transcript

Crystal Gail Fraser

My name is Crystal Gail Fraser. With Paul Andrew, I am the co-host of How I Survived. This is a podcast about recreation at residential and day schools in northern Canada.

In this episode, you will hear about abuse and trauma. Please look after yourself as you listen.

If you are a Survivor or intergenerational Survivor of residential or day school and you need help, there's a free 24-hour support line. Call 1-800-925-4419.

Agnes Kuptana

I'm Agnes Kuptana, and I'm from Ulukhaktok, Beaufort Region, NWT. And I went to residential school when I was six years old to Coppermine Tent Frame Residential School. After four or five years of it, back and forth, we went on to Cambridge for a bit, Cambridge Bay, Nunavut. Before that it was still NWT. And then we went on to Stringer Hall Residential School in Inuvik, under Sir Alexander Mackenzie School.

Crystal

Agnes Kuptana is a residential school Survivor. She’s also a talented seamstress and educator. Listeners of the How I Survived Podcast were introduced to Agnes in our first episode. Agnes made the wall hanging that is featured in the cover art for the How I Survived Podcast.

When we approached Agnes to create a wall hanging for How I Survived, she told us that she also wanted to be interviewed. As you’ll hear later in this episode, Agnes wants young people to know about her experiences at residential school.

In September 2023, Agnes and her husband, Robert, travelled from their home in Ulukhaktok to Yellowknife to be interviewed by Paul Andrew. Yellowknife is in Treaty 8, on the homeland of the Yellowknives Dene and the North Slave Métis.

Paul Andrew

Agnes, can you tell us what your life was before you went to residential school?

Agnes

I was born and raised in an iglu in December 15, 1949. And we were raised out on the land, following other animals. During the four seasons, spring, summer, fall, winter. You're never really in one place. And it was beautiful. There was no sickness. People eat healthy, people shared. They get just what they need to get and share because of the cold, cold winter we grew up with–minus 60 to 80 below, which we didn't mind, because we were in caribou clothing in a way back then. And we had warm iglus with seal skin, seal oil that heated our qulliq.

Our qulliq is a stone lamp. They may be big. Some may be small. But they have each two or three in each iglu. That would give us, the seal oil would give us, the qulliq would give us light, heat, cook our food, dry our clothes.

And, it was all in a language. There was no white people. The only time you see them is when you go to Holman, which was called Ulukhaktok before then, to go to the Hudson Bay, or to go over to the Roman Catholic Mission to get your ears checked, your throat. That's the only time we see white people. We don't really bother with them because we're from out of town and we fear. Because we've never seen white people before, and they look different, and they're not our kind. We may say hello, but we're distance, we're long distance from them. They may be friendly and that, but we don't know them yet. Not long enough to stay. We might just stay a day, get a few things, just what we need, and then we head back to the camp.

Paul

Now when you were growing up on the land, who were your teachers and how did they teach you?

Agnes

Our teachers were our parents, mum and dad, aunts, uncles, grandparents, grandmother, grandfather, and your cousins, your older cousins that look after you in a camp if the families are out, out on the ice hunting seal, or they're up on the land hunting tuktu (caribou), and maybe checking trap lines, few traps that they may have.

It was beautiful. It was healthy, loving, lots of teachings. Every day is different and there was no fear. And it's all in the language. And lots of playing time and learning to do things. Chores, sewing. Sometimes you help your cousins go check trap line, maybe a few traps, and you come back and you help Elders if they want. You hitch up maybe one, two, three dogs and go chop some ice from the lake or get water when the rivers start going in the spring, for their drinking water, fresh drinking water.

And there was lots of growth. There may not be that many animals close by, but there was always something. To every different season of the four seasons we have.

Those were my teachers. And it was a loving, everyday, close-knit family that always have listening hands and helping hands for need.

Paul

And how did what you learned on the land at home help you cope in residential schools?

Agnes

If we didn't have that, we would have been maybe lost, maybe trying to walk home. It gives you strength and hope that one day, one day, they're not going to have us here all the time. One day, we'll be going back home. And we look forward to going out on the land, eating our country food, preparing it, and hunting it, and sharing it. And the laughter, and the love that you see every day. Everyone was like teachers that are knit together, like a family. Even if they are strangers from different villages, they were like one family. And that's what gave us strength to keep going.

Grandmother always make a fire outside cooking and she says to us to go pick up some driftwood or any wood that's growing old and snap them off from the hillside. So we're walking up and we started hearing a plane. Why would this plane be circling? And we didn't mind it. We didn't bother with it because we don't worry about airplanes, but it just kept going round and round. So my grandmother yelled at us to come back down. So we went and with little what we picked up we brought. And they landed and that's when they came to pick us up to go to Coppermine Tent Frame Residential School.

The floor is just wood like this, so when you walk you could see bottom. All it had was four beds with a small stove with an oil, oil little tank in the back there in the middle and an opening where you can open and look out. And a door, which wasn't safe. The beds were just a sheet, blankets. So you can imagine if we did not sleep with our clothes, our parkas, our mitts, our mukluks, and put our hoods on, we would have freezed to death. You hear children crying at night cause they're freezing.

Crystal

The Coppermine Tent Hostel began regular operations in 1955. Located in what is now Kugluktuk, Nunavut, the hostel was operated by Anglican missionaries.

From April to August, children lived in canvas wall tents stretched across wood frames. As Agnes describes, the tents were drafty and hard to heat. They were also easily damaged by high winds.

Initially, the children at the tent hostel came from the Kugluktuk area, but eventually, children from as far away as Ulukhaktok were brought there. The children attended classes at the local federal day school.

When the hostel closed in 1959, most of the children were transferred to the new residential schools in Inuvik.

Agnes

When I first went to Coppermine Tent Frame Residential School, I didn't learn not one thing for a whole year that I was there. There was a lot of fear. A lot of crying. Homesick. Your country food.

I used to think that, as small as I was, my parents iglu was just over the hill. So I tried to go walk and look, and if I did not turn back, I would have been frozen to death. But it didn't look the same, didn't look the way, the land didn't look the same. Then they were not there, they were not there for me, even you call them by names. No one was answering.

Paul

Now, tell me a little bit about your time at residential schools. What kind of sporting events or recreational activity did you do when you were not at school?

Agnes

Sometimes they may, somebody may start catching ball or maybe a small baseball. Or another time somebody comes up with a ball, then they say, “Andy over,” where you're throwing the ball to the other side, and if they catch it, they run around and hit you. And if you got hit, then you go to their team, they take you away, and then your other team will have to try and get you back. And it was called Andy Over.

Another one was hide and seek, but that was a bit scary because you do not want to go too far from the places because you don't really know the people, even though they tell you, you are related to us through your grandparents. And it's all in the language.

Whatever we speak in the school or in the kitchen or dining room, then I don't know why we get hit for it or even turned to a corner for a period of time without eating your food. So we learned how to be silent. We learned not to speak when you see white people nearby. Because if you do…

Paul

I know when our time at residential schools, sometimes we played pool, other times we played games, and other recreational activities like that. Did you spend a lot of time doing those things?

Agnes

No. When we're back in our tents and we maybe get together outside, as a few children that know each other, then we may turn into our own games, such as Ma'na Ma'na Me or we might go into string games, or we might just listen to those stories of how someone is thinking of their parents at this time of the year, what they're doing, and look at us, we're stuck here.

But we always try to encourage each other to say that in the language that we're not going to be here all the time. We feel like prisoners, somebody taken away and not to see your parents for so long. And then we say that spring is coming. And maybe one day that we'll go back. Then there we go, out on the land. We're always out on the land. Busy, like we never stay in one place.

Paul

So, some of the things that you did at residential schools, were they similar to or different than what you did at home?

Agnes

Very different. Every day you wonder what's gonna happen to you. You wonder if we should even try to get up and face another day of being abused, being strapped. And that finger is pointing at you saying. After what they do to you, they telling you never to tell. No one. Never tell no one. Never knew what it meant. And you fear of those fingers, the big hands you see.

I was sexually abused. I was strapped. I was put in corners. And I used to think, am I really a bad person? I don't know because when we were growing up we were taught to love, and to share, and to be there for someone that needs you, and to hold hands, and laugh.

But in those residential school days, we were like, we were prisoners. You keep your distance, you fear when they come close to you. And sometimes you hear children crying to sleep. And no one to really talk to, except your older siblings or a cousin that's there.

And I used to see this Anglican minister that do come. And I used to think to myself, if he's an Anglican minister and works for people, and knows the word of the Lord, then why does he stand there and not help the children that are suffering? I used to think that there's something not right.

But, if I did not forgive my abusers and these people, then I would never be here today. I would have been a long goner, just like everyone else, but I have to learn to forgive, to carry on for myself and to move on, find someone and have children. Grandchildren. If I didn't think of them, then I wouldn't have been here. I had to learn to forgive. And carry on. And deal with it. Make myself stronger every day. If I didn't have my creative for every day, then I wouldn't have been here.

Paul

I want to ask you about either sports or recreational activities in residential schools. Do you think it had a positive or negative impact on you?

Agnes

I would say negative impact because it's like they're always yelling. And when you do not do something right right away, you're told to go sit down. Then you used to think, what did I do wrong? I tried to be as good as the others and do what they're doing. And if I didn't do something right, then I get yelled at, and I have to go sit down.

And you see other children, who are so active and laughter. And then when they come in, it's like they're distance, like they want to stay by themselves. They don't want to listen, like, they don't want to come to try to play what they want them to do. I can't remember what activities we used to have for sports. It wasn't very big. The school wasn't very big. It was always like they raised their voice. That's what made the younger ones fear.

Paul

Let's talk a little bit about after residential schools. You know, when I talk about recreational activities, cultural activities, drum dancing, singing, getting out on the land.

Agnes

The only way we did not forget our language was. We were afraid to talk or speak it when we were in classes because we would get strapped for it. We would get punished for it. When school is over, we would get together some place where we would not be heard and we carry on our language. That's the only how we did not forget it. We may have forgotten a few words, or have not heard it for a long time. And forgot how to really properly say it when we go back home. But that's how we try to cope with carrying on as one. With the strength we had and hope to carry on every day.

Paul

What about things like drum dancing? I know you guys are involved quite a bit with some of the cultural activities.

Agnes

Yes, drum dancing was a really big part when I was growing up. Our people were thankful. When they have done their hunting, or their spring hunts, their fall hunts. In winter months they don't really go too far, too much long ways.

Drum dancing was something I grew up with, listening to it, and it's all in the language. People are making up their own songs. What they have done today, how thankful they are, what they have caught. They make a song out of it while they're still coming home, and then they want to share it and it becomes a song.

I'm sorry I did not bring my drum. I have my songs at the hotel room. But you see how powerful they are. Making up those songs, and listening to those songs, and sharing those songs. It's healing, it's so powerful, and it's all in the language.

And sewing is another thing that we learned while growing up as small children. We learned to make miniature things such as mittens, little mukluks, little parkas. So, one day, when there's enough hides to spare, then we can get into bigger items to make things for our brothers or our sisters, our siblings.

And the language and the stories was another big thing that we share from our grandparents. They gather us and they tell us the stories of how they grew up and where they grew up and where they're from. And what it was like back then to now.

But it was a big different out there than what we have today. There was no sickness. There was no phones. There was no computers. There was no TV. There was no airplanes. Maybe just a few schooner boats. The jolly boats that they have, the wooden ones, with the three-horse kickers. It was a healthy life. It was a loving life.

Today is so different, but our young people, our children, our grandchildren especially, are living two lives. We're trying to teach them the cultural ways, our traditional ways, which were taken away from us when we were in residential school, which we could not share or use our knowledge, but we did not forget our language. That's one strong thing. Then we came home and our parents are there to hug us, to take us back to the camps. And knowing that we still can understand and say some words. Not the proper way in some wordings, but we are trying.

Drum dancing and sewing and our cultural, our traditional ways was very powerful. We still try to carry them on today. Taking our youth out on the land programs, our Elders. I'm so thankful.

Paul

Agnes, what would you want recreational leaders in our communities in the North to know about your experience in residential schools?

Agnes

I want to be able to share what I've gone through so our youth today can learn, and the younger ones can know how lucky they are today, how safe they are today, and what it was like for us back then, what we have gone through, what we have suffered through.

And to turn things around and have drum dancing, maybe square dancing, or maybe a baseball, or maybe a soccer ball. Any recreational activities that will make them gather together and to enjoy.

When you're drum dancing, you forget about everything. You forget about what happened yesterday. The loss, family losses, or the hard times that people had. The sickness, the COVID. It's so powerful. And you don't just do it to show your steps off. You show it from the love you have and what you have experienced so that you can pass it on to a younger generation. And they are learning today, the little ones are. And they're into it.

I want to be able to share all this and to be heard. We were once taken away and what happened to us behind closed doors. We have come this far and we have healed. We still have healing to go through, but one day at a time.

Paul

How important would you say recreation is? To your children, grandchildren, to the little ones that we see, how important is it?

Agnes

When they see laughter, or the babies hear laughter, or they're playing and they want to take part, you don't hold them back, you let them go take part. Even if they don't know how, you show them. Sooner or later, it will click in their heads. Even when they go home. They are trying something that they have learned. You see your grandchildren come home from school and they learn language or drum dancing or a different game. They are telling you they are proud of it.

Paul

You know, Agnes, I asked you a whole bunch of things that we wanted to know. Is there anything I didn't ask you about that you want to share with us?

Agnes

Was there any hope back then? Was there any love back then? I did not see that when I was going to residential school. It was a lot of abuse. But somehow, we were there for each other.

When we see a child crying, that's been abused, we don't let them be alone. We take them. We sit down with them. We don't ask them questions, we just hold them till they are ready to say something. And say, “You know, let's do something. Let's go for a walk. Let's go see an Elder. Talk to them from distance.” Cause you have some Elders that have some houses far from the residential school area. And they're outside, always outside doing something. So even if we didn't have sleds, we would try to go sliding, maybe go run, hide and seek. That's recreational. Trying to get something going to make them happy again.

Because they were happy children, but when they go behind closed doors somewhere, they come out hurting. And we do not let them be alone. When you turn something around and want to do things, you make them smile and they start to laugh and they want to join. You know, they forget about it. But sometimes you hear them crying at night, middle of the night, because what had happened. They're dreaming about it, it's fearing them. I went through all that, I've seen all that, but trying to put happiness and laughter and do fun things, turn things around, and that's recreational.

Maybe hopscotch. Maybe baseball, maybe prisoner base, hide and seek, long run. However you want to play things that's away from the group that was maybe at the kitchen, dining room. If they're in their own place and they're doing things among themselves, then that gives us free time to get together.

Paul

You know, for me, sports was so important in residential schools. Otherwise, I wouldn't have. Because I really had problems.

Agnes

It wasn't just all sports for us. Sometimes you can just go, maybe pick flowers. Or go pick a bit of berries.

Paul

Agnes, powerful. Powerful. Thank you.

Agnes

Ilaali. Qujannamiik. Quana. Quyanainni.

Paul

Quana.

Crystal

Agnes Kuptana wanted to be interviewed about her time at residential school because she wanted young people and future generations to know what she lived through.

Agnes’s story is hard. It is marked by abuse and trauma. It is also a story of strength and persistence.

In her interview, Agnes shared that, in general, recreation had a negative impact on her life at residential school. But some of Agnes’s memories of recreation are different. She recalls, for example, the ways that she and other students used recreation to care for one another when they were hurting. Often, these were outdoor activities like going for walks or sliding, or activities that reminded them of home, like string games or picking berries.

This podcast is called How I Survived, but as Agnes's story makes clear, survival was a communal endeavour. Children made it through residential and day school because they looked after each other.

I want to thank Agnes for sharing her story with us. You can see pictures of the wall hanging that Agnes made for the How I Survived project, as well as other photos of Agnes’s artwork and crafts, on our website, www [dot] How I Survived [dot] ca.

If you are a Survivor or intergenerational Survivor of residential or day school and you need help, there's a free 24-hour support line. Call 1-800-925-4419.

How I Survived is a collaboration between the NWT Recreation and Parks Association and the University of Alberta. The podcast is co-hosted by me, Crystal Gail Fraser, and Paul Andrew. I also provide historical direction.

How I Survived is co-produced by Amos Scott and Jess Dunkin. Advisory support is provided by Dr. Sharon Firth, Lorna Storr, and Paul Andrew. Our research assistant is Rebecca Gray. And our audio engineer is Brandon Laroque. Haii’ to EntrepreNorth for sharing your recording booth with us.

Our theme song is “Love the Light” by Stephen Kakfwi. The cover art for this podcast was designed by pipikwan pêhtâkwan based on a wall hanging made for the project by Agnes Kuptana.

This podcast is produced with support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and NWT and Nunavut Lotteries.